|

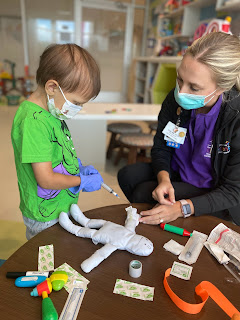

Phin performs a procedure on a "patient" in the Children's Hospital playroom under the supervision of Child Life Specialist Kylee. |

When Phin first went into the hospital and got diagnosed with AML, as soon as I could pull myself together a little, I went on a long walk with our neighbor and good friend, B________, whose son fought leukemia into remission several years ago. I was having trouble putting the experience and all of the associated feelings into words. The two of us walked several miles together that day, and as we talked I was reminded that with cancer, there's often a wide gulf between the technical and the abstract. I found myself in that gulf. I could parrot the oncologists' explanations of the science of the disease and its effects, but since I'm not a medical professional I wound up giving hollow explanations and hoping that my friend didn't ask any specific questions. Or I could forge a comparison and talk about how it's like something else that I've experienced or observed.

But cancer isn't really like anything else. It's only like cancer.

On our walk, B________ and I compared our cancer field notes. Hers were much, much more extensive than mine. Her son had fought a different kind of leukemia than that with which Phin had just been diagnosed, but the language of leukemia was common even if the dialects differed slightly. We talked about blasts and platelets, about CVCs and bone marrow aspirations and transfusions and transplants. But eventually, inevitably, we veered into metaphor territory. I needed her to help me process what it felt like to have a child be diagnosed with a disease so terrible and deadly.

"I feel like I've been blown apart," I said. "My whole body aches and my feelings and my thoughts are all over the place. It feels like I'm picking up little bits of myself and trying to fit them back together but they aren't going back together the way they were."

B________ nodded.

"It's like suddenly having to be really good at something you haven't been paying attention to or practicing, and knowing as you do it that your child and your family's well-being depend on it."

"Yes," I said. "Like, go and do a sport, right now, where you have to win, and your opponent is fast and ruthless, and your team is depending on you, and also it's the championship game, and you've never played this sport before."

"Yeah, or 'Here, land this plane,'" she said.

On and on like this as we walked. Sometimes, when explanations and comparisons failed, the silence was broken only by the sounds of our footsteps and my occasional sobbing. When we finally arrived back at her house, her son, who has survived leukemia, came out and hugged me. As I turned to walk back to my own house, I glanced back at the two of them. I had no comparison to make for their bravery and perseverance, but suddenly I did have a goal.

|

Phin being a total champ about taking his every-six-hours eyedrops. |

What I have realized since then is that while there is still nothing comparable to cancer or watching a loved one fight it, for me there's much less agency involved than I ascribed to myself in my opening salvo of metaphors. All of the heroic sports moves and piloting is done by the nurses and physicians.

Right now, it all feels more like a boat ride through total darkness. There's the sensation of movement--possibly even forward motion--but it's impossible to see what's ahead. Are we passing under branches with dangling serpents? Scraping hidden rocks? Drifting toward a waterfall? Each morning, a daily labwork report sounds the depths, but aside from that and the vague sense of momentum, the rest is darkness and silence.

Medical Updates

This round, Phin had chemo every 12 hours for five days, and now that's over and he's doing what's called "count recovery." Here's what that means, as I understand it.

After the chemo nukes his system for however many days (five this time), he stays in the hospital for another month(ish) to a month-and-a-half while his body restores the levels of ... things ... in his blood to something that resembles normal (for him). Then that round will be over, and he'll get to go home for about a week, and then he'll come back and do it again.

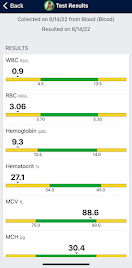

For example, check out these screenshots from the past three days of Phin's chart, paying closest attention to the bottom field, which is platelets:

White blood cells are the things in the blood that fight infections. Like his platelet count, Phin's WBC count falls as the chemo drugs target and destroy rapidly dividing cells all over his body. The bounce in red blood cells (RBC) resulted from a blood transfusion after the 6/13 labs. Thanks to some generous blood donor out there--possibly one of you--Phin received a fresh bag of blood and spent the next 24 hours in beast mode. Now he's gradually coming down again.

This is what count recovery looks like. His numbers slide down, down, down, until they reach a certain threshold, at which he receives blood products (thank you again, donors!), revs back up, and stays alive, then down, down, down again, then more blood products, again and again and again over the course of several weeks until he reaches the point where his numbers stabilize. Then, after a quick visit home, he comes back and gets nuked all over again.

Only harder.

|

One boy, two wheels, and barely any platelets. |

Even when his counts are low, Phin is still tough to keep up with. He zooms around the unit and the

playground on his bike full tilt regardless of whether he has any platelets or not, filling his healthcare team and parents alike with a strange mixture of admiration and horror. To my knowledge, there is no word in the English language for this emotion. Today I watched him rocket through a doorway and almost collide with a food cart when he knew full well, as much as a five-year-old can, that he had approximately four platelets in his whole body. I admired him. In abject horror.

He's also doing a lot of drawing and coloring, reading books, playing with puzzles and toys, and watching TV. He's been practicing some basic sight words on the whiteboard in his room. He's also been building more blanket forts and arranging his animal toys around his room as if they're in exhibits in a zoo. He gets cranky sometimes, but overall, his moods are super-positive. He seems completely comfortable and relaxed at the Children's Hospital. While he may not feel like he "belongs" there necessarily, he absolutely feels a sense of "belonging" there. In other words, does he feel like he should be in the hospital instead of somewhere else? Questionable. Does he feel accepted at the hospital? Absolutely. That speaks to the extraordinary work performed by the many nurses, child life specialists, staff members, and physicians who populate his world and make him feel loved and cared for there.

|

One of the cardinal chicks near its nest in the hospital playground garden. |

it begins to cool down a little.

I think there's a kind of beauty in that. I can't stop thinking about it.

Google says you're looking for the word wynorrific! Not a real word but if enough people use it to mean beautiful or pleasurable and horrific at the same time, it may become a real word eventually.

ReplyDelete