June 1, 2017

My parents stopped into the hospital where I’d been admitted, pregnant and ready to deliver our third child who had decided to come a whole week after his due date. "Babies come sooner and faster with each one you have," people had warned. In our case, each child came later than the last: Av had been a week early; Obelia—never to be outdone—surprised us by being one of the 5% of babies who arrive directly on their due date; baby number three was taking its time.

|

| May 31, 2017: one week past Phin's due date |

Like the others before him, we didn't find out whether Phin would be a boy or a girl before his birth. People would often see me with my round third trimester belly, holding my two daughters by the hands, and say, "Finally getting your husband a son." I never felt more akin to an heirless queen before, but the truth was that we liked the surprise and didn't care what sex our children would be; we just knew we wanted three.

My mom paced nervously at the end of the bed; Papa sat straight-backed at the edge of his chair; Dustin stood by my side remembering not to crack jokes by threat of death. All three tried to keep me distracted while we awaited the arrival of a doctor, a nurse, someone—anyone, really—who could deliver the steadily coming baby. "I…have…to...push." I squeezed Dustin's hand. The epidural had failed; someone had smashed some glass on the floor sometime during the process, and I could feel, much to my mild disappointment, everything I never wanted to feel.

Mom ran from the room, calling for a doctor. I locked my gaze on Papa, sitting stiffly in his chair, and said: "If someone doesn't come soon, you're going to be delivering this baby." He stiffened further.

My father, a reluctantly retired ENT, had regaled us with stories throughout my childhood of his med school days in Germany and his residencies in America thereafter; he'd tell us about choosing not to go into obstetrics or gynecology (because of the unpredictability of when babies would be born) or any mental health field (his test scores left something to be desired in those fields). I could tell by his tense posture that delivering his newest grandchild was the very last thing he wanted or ever imagined he might have to do when he swung by to see me on his way out of town to celebrate his 75th birthday with my mother. As luck would have it, Mom appeared, pulling behind her a stunned-looking doctor straight from an examination room.

"Do I have time to..."

"You have time to do nothing," a nurse interrupted the doctor, pulling back the sheet from across my knees while another nurse tied on the doctor's gown.

Moments later, my father was given the greatest 75th birthday present he could imagine: his third and final grandson.

|

| Phin and PePop, June 1, 2017 |

May 31, 2021: Memorial Day

Our neighborhood popped with summertime feels: kids in denim shorts riding bikes and scooters, tearing down the streets from one house to another in search of Memorial Day Scavenger Hunt clues, streams of melting orange ice pops crawling down hands and chins, the distant sound of a pool radio belting out a country music tune while shrieks of jumping swimmers rang out across the neighborhood lake. I had just finished handing around plates full of burgers, baked beans and roasted veggies that Dustin pulled off the grill to my own three exhausted, red-faced kids when my mom called. My dad, now 78, had been feeling sick for the last week or so: vomiting, fatigue, lack of appetite, extreme pain in his back and stomach. He'd lost weight and had almost no energy to do anything.

In retrospect, he would say that he remembers the exact day he began to feel bad—after a long car ride from Florida on Nov. 1, 2020. He got out of the car that day and his back ached. It never stopped. Within twenty-four hours of my mom calling, asking me to come drive them from their home in Hilton Head to our hospital in Savannah, my father was diagnosed with cancer. Multiple myeloma. And it had taken up residence in his back, gnawing away at the bones of his spine.

|

My dad, Papa, far left, with his parents and siblings.

|

I like to tell people how my dad was born in a colonized India and was raised bilingual under British rule. How he spent his formative years living with his uncle in India while his parents lived in Tanzania, Africa, still under British government. After India, he moved to Germany for med school, but he didn't speak a word of German and had to read and translate his medical textbooks using a series of dictionaries that spanned several languages: German, Latin, English, Marathi. I love to try and retell how he worked in a brandy factory during his time in Germany, met native German friends at the pub once a week where they'd alternately teach each other German and English. How, once, he and his friends purchased a dilapidated old car so they could travel. It had a hole in the floor and broke down on a German road; they ended up spending the night laughing under the roof of the mechanic's home with his family who invited them in and out of the elements.

Later, under his father's advice, he came to America, met my mom in New York City, and thwarted a marriage his father had been arranging for him back in Africa. He came to every extracurricular activity my three siblings and I participated in—sometimes driving an hour to catch the last few minutes of a soccer match or baseball game, sometimes being called onto the field if someone took a ball to the face that had knocked out some teeth or given them a concussion.

On rare late nights, after saving dozens of patients or losing one, he could be found with a snifter swirling a thumb of blackberry brandy, sitting in his study, his stoic face the only thing aglow in the dimly-lit room, spotlighted by a single-bulbed lamp.

|

Papa in Germany with his friends and

the infamous broken-down car.

|

When his cancer diagnosis came last summer, his affable, optimistic disposition grew somber and quiet. The man who had spent his whole life devoted to caring for others now found himself in need of care he wasn't sure how to receive. It was also the first birthday since Phin was born that the two birthday buddies wouldn't spend together, a fact that didn't go unnoticed, even by a thee-turning-four-year-old Phin. That year, we sang and Phin blew the candles out twice: once for himself and once for his PePop.

|

| PePop and Phinny napping |

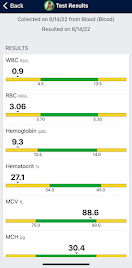

Each time in the past year since his diagnosis that Papa has caught a cold, it has landed him in the hospital. His immune system can't take a single thing we throw at him. This year alone, I brought home Covid, right at Christmas

—a holiday we'd been planning to spend with my parents. My girls brought home colds, viruses, the stomach bug, mono, and Influenza A. Schools are rampant with quickly spreading germs and all five members of this Michael family exist most of the year inside the walls of a school. Our visits to my father have been cautious and few, and on them we often keep our distance, even when we're near, afraid we will carry to him something his immune system cannot fight. Now our caution has expanded to not one but two June 1st babies.

Papa tells me "I feel so old, like I've aged by ten years in the span of one." He's tired; his body is tired. It has become harder to coax from him the tales of his youth, a smile, a laugh. Harder to pull him back from the dark despair, like a black hole, that continues to collapse in on itself again and again, consuming the light. Some visits, I've found him, curtains drawn, lying alone in his bedroom, the sound of children playing just outside his door. He's listening, a small smile in the dark; I curl up beside him, hold him tight and pray for more time, pray thanksgiving for the time I've had, pray he knows how much he's done—how much he's mattered—for the lives of so many others, for me, for Phin, who insists that his own middle name is "Kishore" after his grandfather, and doesn't let a birthday pass where he doesn't expect PePop to be right there with him blowing out the candles.

|

PePop making Easter "empty tomb rolls"

with my babies |

When we received Phin's diagnosis, something broke in the center of my chest. I felt it every moment like a black hole collapsing in again and again, sucking everything with it—my ability to eat, to feel hunger, to think, to remember, to sleep, to close my eyes when I crawled into a bed to try to sleep, to breathe without effort, to walk without feeling how heavy my gait had grown. Sometimes, I'd stand at the stove, making pancakes for my girls on a Saturday morning--trying to will back the feeling of a regular Saturday morning during the before times when we'd all be eating and making pancakes together—and the moment would suddenly be struck by thunderbolt-sobs followed by a daughter's hand frantically grasping my waist, her voice whispering: "Mama, don't cry" as she'd bury her head into my shirt and cry, too.

For days, I expected the black hole to grow, to fill my chest then arms and hips and legs, to swallowing me entirely, to take me in like it had taken my father. I listened to my girls sleepy breathing at night, a mantra reminding me: in and out and in and out...

Something broke in all of us. But, despite that, my parents and brother came to help. Mom buzzed around, propelled by her grit and survivor's strength, cared for all of us, kept the household running. My brother shuttled the girls to school, activities, brought them for special treats. My father huddled silently on the couch wrapped in blankets, sometimes teary-eyed, other times watching me from across the room, sometimes startling me in the early morning hours—hours he likely hasn't seen since his on-call days—when I thought everyone still slept. He began to offer words again: "He's strong." "The odds are in his favor." "He's only four. Pediatric patients have better outcomes."

Some days, when the girls had gone to school and the morning was still dark, in the sleepiness of the house when I thought myself alone, I let gravity take me wherever I fell: the tiled kitchen floor at my feet, the stairs at my knees, the couch on my face. I wept with anger, sorrow, despair, prayerfulness, desperation into the cushions. Then out of the darkness, feet shuffling closer, blankets falling way around him, the comfort of my father emerged, his hand on my back—he will be okay; we will be okay—a salve to close the collapse, to heal the hole; my father guiding us both, slowly, back to the light.

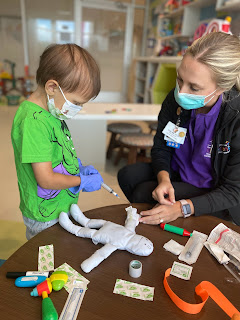

Phin and PePop see each other for the

first time after Phin’s diagnosis